First Anglo Afghan War Auckland's folly – An expedition in Regime Change (Page 1 of 7)

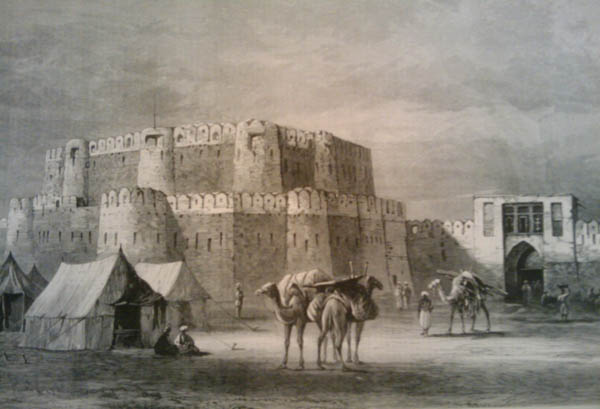

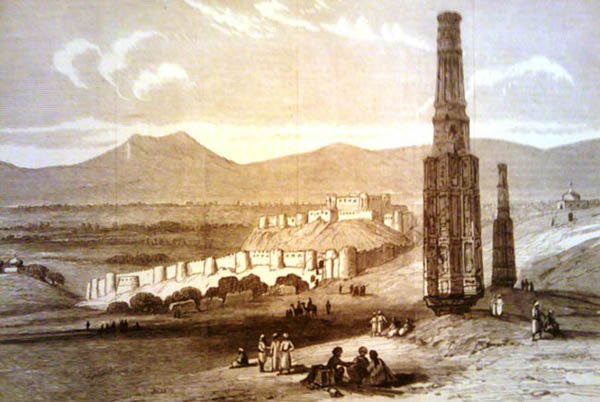

Figure 1 ILN 1880 Citadel of Candahar with the Principal Gate £14

The first British contact with the Afghans had been through the Embassy of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone to the Court of Shah Shuja in the Afghan winter capital of Peshawar on 25th February 1809. The beautiful wooden durbar hall where the meeting took place no longer exists since this was deliberately destroyed by a Sikh soldier during the Sikh occupation. However, Elphinstone is still known to us for his perceptive work the

Kingdom of Caubul first published in 1815. Regretfully those making decisions to invade Afghanistan should have read this book more closely before deciding upon such an unwise action. Elphinstone recognised that a foreign invasion and oppressive foreign rule would not be tolerated by the proud Pashtun tribes, who would fight for their liberty no matter what the cost,

“Their vices are revenge, envy, avarice, rapacity and obstinacy; on the other hand, they are fond of liberty, faithful to their friends, kind to their dependants, hospitable, brave, hardy, frugal, laborious and prudent.”

The tribes spent most of their time fighting each other, but they swiftly combined to repel any outsider and were ever

“ready to defend their rugged country against a tyrant”.

Today the Americans have risen to the challenge that the British in the Nineteenth Century and the Russians in the Twentieth Century failed. It is clear that the high water mark of Pax Americana has been reached in the mountains of Afghanistan and that the 21st Century will be the Century of defeat in Afghanistan for America’s imperial ambitions.

After the 11th September 2001 attacks on the USA the American Government decided to replace the Taliban’s Goverment of Mullah Omar with a former Unocal employee, Hamid Karzai who would be more likely to further US aims in the region. Similarly in 1839 the East India Company decided to replace the Amir Dost Mohammed with the former Saddozai Afghan Amir Shah Shujah. Shujah had been a British Pensioner at Ludhiana since 1816 and was keen to regain his Kingdom from his step Brother the Barikzai, Amir Dost Mohammed. The reason for the decision to replace the Dost was based on the fact that the Dost had received a Russian Diplomatic Mission at Kabul, which was headed by one Ivan Vitkevich in December 1837. The East India Company feared that the Russians wanted to advance on India via Afghanistan and so required a staunchly pro British Amir on the Kabul throne and Shuja was considered ideal for this function. For this reason an army, styled with the title of the “Army of the Indus” was assembled including camp followers. The ill fated invasion of Afghanistan commenced in 1839 crossing the Indus and entering Baluch territory via Quetta into Afghanistan.

During the First Anglo Afghan War the troops of the East India Company styled as the “Army of the Indus” struggled through the arid deserts of Baluchistan finally arriving at Kandahar. To British relief the city was not defended by the Army of Dost Mohammed. The Brits rejoiced, because they were thirsty and hungry and could not have succeeded should the Afghans have fought in defence of Kandahar. A British Lieutenant wrote in a letter dated 20th August 1839 as follows:

“we arrived starved and way worn at Kandahar and happily, there the enemy did not make his stand- we could scarcely drag out guns our cavalry could not go faster than a walk and if we had then been obliged to fight the result would have been dubious- if dubious –but mention not the word defeat for disaster to this expedition would have been almost ruin to the British dominions in India- we have done the trick, and alls well that ends well.” (Gaisford)

Figure 2Interior of the Citadel of Candahar 14-8-1880 ILN £14

Figure 3 Accident on a mountain road as Brits struggle with the difficult Afghan terrain £12

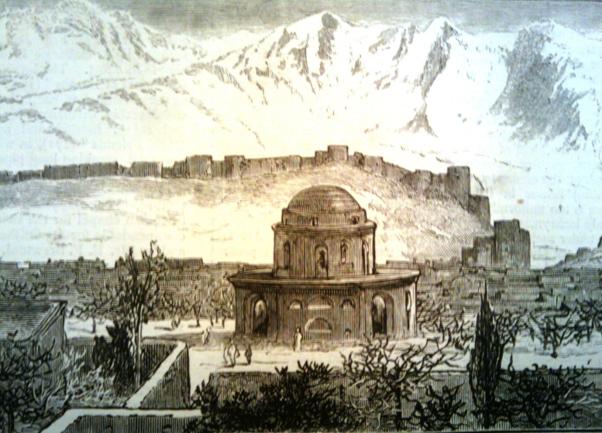

Figure 4 Ghazni Minarets and citadel £14

The town which established an Empire, the Ghaznavid dynasty and produced cultural epics like the Shah Namah was sacked three times, by the Ghorids, the Mongols and by the British in 1839. The Ghorid and Mongol depredations left behind the very visible Ghaznavid legacy of the two famous minarets of Mahmud, as the only surviving remainders from a large Ghaznavid Mosque. These minarets stared down on a new foreign attacking force which would devastate the Afghan defenders on 22 July 1839, as well as the morale of Amir Dost Mohammed and his troops. The attacking British force discovered from an Afghan traitor that a particular gate of the Citadel was not bricked up and so was the most vulnerable entry point to the Citadel containing the old city of Ghazni. So under the cover of a dark moonless night, the gate in question, which had not been reinforced was blown open with an explosive charge by Lieutenant Durand. Durand is of course famous, since he would later give his name to the Durand line dividing Pashtun territory between Afghanistan and the then British India. The explosion caused by Durand’s efforts, led to a breech in the citadel defences. Through this breech the attacking force entered and prevailed after bitter hand to hand fighting against the Afghans. Fighting was so fierce that the husband of the famous Lady Sale, General Sale, fought desperately with an Afghan defender who was on top of him and of much greater strength. Sale called to a fellow Officer to stab the Afghan with his sword, which the Officer did but then unluckily for Sale went on his way without establishing that the Afghan was no longer in a position to fight Sale. Sale continued to struggle against the strong Afghan who fought on gallantly until Sale delivered a death blow from his sword to the Afghan’s head(page 104 Signal Catastrophe P Macrory. With the end of fighting at Ghazni the attention of the invaders now turned on to the defenceless Afghan females as the British heroes decided to enjoy the remainder of the night,

“ You soon saw Cashmere shawls, ermine dresses, and ladies’ inexpressible over the bloodstained uniforms of our men- the poor women themselves, in some instances dragged out(J.C. Stocqueller, ed ., Memorials of Afghanistan (Calcutta 1843))”.

The victors of Ghazni it seemed, appeared to think that draping women’s underwear over their uniform was a macabre badge of their new status as rapists. Chivalry was an alien quality to this invading army. The defenders of Ghazni had been a multinational lot, including Bengali and Indian Muslims, in a situation very similar to the defenders of the Taliban’s Afghanistan, which included British Pakistanis, Pakistani Pashtuns as well as an assortment of Central Asian nationalities and of course Arabs. In fact journalists and the ISAF forces were shocked to even discover a young American Talib John Walker Lindh, subsequently imprisoned in the mainland USA.

On the road to Kabul the British force was repeatedly attacked by Ghilzai tribesmen.

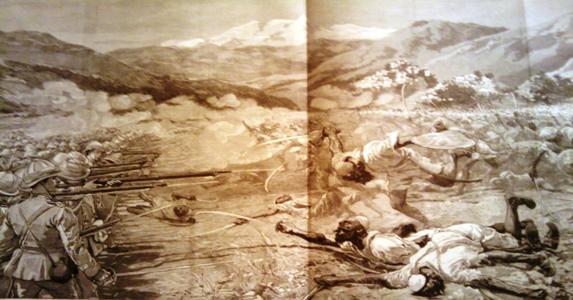

5 Pashtun warriors advance against the armed enemy invaders double page spread £18

Figure 6 Bala Hisar(High Citadel) where the Ameer’s Palace was situated, and which, strongly fortified commands the whole city-being in fact a town within a town, and containing 5,000 inhabitants for its own share of the 60,000 citizens of Cabul. A portion of the city of Cabul is also shown with the village of Deh Afghan in the foreground by Lieutenant J Burne-Murdoch Royal Engineers May 1 1880 The Graphic £14

After the British force took Kabul, Shahmamat Ali an Indian serving the East India Company as a Persian translator An Expedition to Kabul Chapter 18(John Murray) 1847), reports that an Afghan man was sentenced to be hung because he had murdered his wife. The murder victim had committed adultery, which led to the husband killing his spouse. The foreign occupation of Kabul had caused inflation in bazaar food prices and women needed to provide for their families and get the money to do so, in any way they could. This situation meant that the British did not endear themselves to the Afghan men. Adultery and female prostitution was not uncommon in Afghanistan at this time. Surprisingly this breech of traditional sexual morality was not restricted to the lower classes. For example, during the occupation of Afghanistan the father of Colonel Robert Warburton, had married a Durrani princess who was the niece of Amir Dost Mohammed. Rather more surprisingly this Princess was in fact already married to an Afghan and even had an Afghan son whom she took with her back to British India.

|

|

(Kaye quoted by Macrory page 122, 1966). The British began to settle down to a comfortable life in Afghanistan enjoying skiing on frozen lakes and boat trips on the same lakes in the summer.

Figure 7 Led to Execution ILN 14-2-1880 by G Durand £15 (Durand incidentally laid the charges at Ghazni to blow the gates open to the Ghazni citadel)

The Afghans could not allow the British to occupy their country and take liberties with their womenfolk. Indeed a similar situation had arisen in the early Nineteenth Century with the Sikh occupation of the North West Frontier. A Muslim religious leader, Saiyid Ahmad Shahid established a resistance base in the Swat Valley of present day Northern Pakistan to combat the wily Ranjit Singh and Sikh power in the Frontier during the Nineteenth Century (See Ahmad, Mohiuddin

Saiyid Ahmad Shahid. The Saiyid was invited to lead the war against the Sikhs because the people were complaining that the Sikhs were abducting their wives and marrying them. The Muslim uprising against Sikh rule in the North West Frontier mirrored exactly what the Brits were now to experience as a consequence of their dalliances with Afghan women. The Saiyid’s uprising met a great deal of initial success including the liberation of Peshawar, the old Afghan winter capital from Sikh occupation.

In November 1840 the Governor of Kabul, Alexander Burnes, whose exploits with Afghan women were notorious was attacked and killed at his residence by an Afghan mob fed up with foreign occupation (See also Burnes, Alexander

Cabool : A Personal Narrative

of a Journey to, and Residence in that City in the years 1836, 37 and

38 written in more peaceful times by Burnes.)

The Ghurkhas protecting Burnes were wiped out to a man and the Afghan women unfortunate enough to be caught in the Burnes’ residence did not survive the Kabul mob’s fury. The stain that Burnes had cast on Afghan honour had been cleansed. A national uprising to liberate Afghanistan from the hated occupation followed. The British Political Agent, Macnaghten, played a Machiavellian role and put a price on the head of the resistance leaders, whilst at the same time attempting to negotiate a deal with the leaders in question. Today we find the ISAF in a broadly similar position stating that they want to negotiate with the Taliban, whilst simultaneously sending their special forces on missions to kill the Taliban commanders.

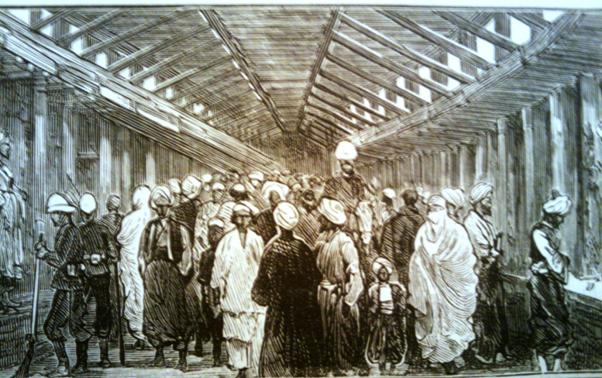

Macnaghten’s dangerous game backfired when the resistance leaders discovered Macnaghten’s plot against them. The consequence was one of the leading lights of the resistance, Akbar Khan, son of the deposed Afghan Amir Dost Mohammed killed Macnaghten for his underhand behaviour. Macnaghten had been hoist by his own petard and his headless body was displayed from a pole in the Char Chatta bazaar, the largest covered bazaar in Central Asia. The Char Chatta bazaar is described as being located at

“the western end of the principal bazaar, and is so named from its covered arcades. The construction of this bazaar is attributed to Ali Mardan Khan of the time of Shah Jehan, to whom are attributed nearly all of the architectural buildings of Afghanistan” The Graphic 1st May 1880.

Figure 8 Char Chatta Bazaar Kabul The Graphic 1880 (destroyed by General Pollock’s avenging ‘illustrious army’ in 1842. £12

After the death of Macnaghten the Brits tried to retreat in January 1842 from Kabul to Jalalabad, but very few managed to make that journey alive. All along the route the army was attacked and slaughtered by tribesmen who sniped at the dense mass of camp followers and soldiers. The Afghan rifle, the Jezail had a longer range than that used by the British and gave the Afghans a distinct advantage. Some British officers galloped away from their men who were incensed by this desertion and shot at their officers (see page 22 The First Afghan War Folklore and History Louis Dupree March 1974

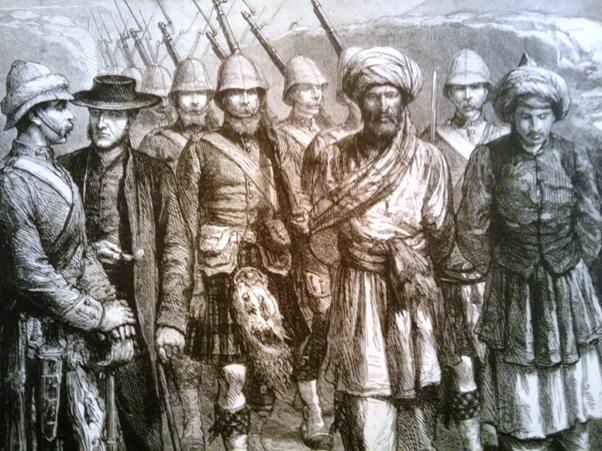

1879 Illustrated London News. Hand coloured Afghan Tribesmen with the long barrelled Jezail for sniping, powder horn containing gun powder and Khyber knife for close quarters fighting. £45

In popular history the sole survivor of the retreat was Surgeon John Brydon, his arrival at Jalalabad is described as follows:

A little after noon on the 13th, one of the sentries of that part of the wall which faced Gandamak and the road from Cabul, called aloud that he saw a man in the distance. In a moment glasses were levelled in that direction, and there, sure enough, could be distinguished, leaning rather than sitting up on a miserable pony, a European, faint, as it seemed from travel if not sick or perhaps wounded, It is impossible to describe the sort of thrill which ran through men’s veins as they watched the movements of the stranger...An escort of cavalry being sent out to meet the traveller he was brought in bleeding and faint, and covered with wounds; grasping in his right hand the hilt and a small fragment of a sword, which had broken from the terrible conflict from which he had come. He proved to be Dr Brydon, whose escape from the scene of slaughter had been marvellous, and who at the moment believed himself and was so regarded by others, as the sole survivor of General Elphinstone’s once magnificent little army. (G.R.GLEIG Sale’s brigade Afghanistan(London 1861 pages 127-138))

However, British officers had surrendered to the Afghans with their wives and later returned to British India including the famous First Anglo Afghan War author Lady Sale. Similarly, Sepoys and camp followers trickled through to India. The famous written account by the Indian Sepoy named Sita Ram (From Sepoy to Subedar 1970 James Lunt edition) details how this Indian soldier was sold as a slave after his capture in Afghanistan but later managed to escape from his Afghan owner back to Hindustan. However, Ram was forever viewed with suspicion by his fellow Hindus, who stigmatised him as being ritually unclean, because they thought he had eaten meat and been circumcised! Others too made their journey to British India, the most curious being the case of John Campbell (see John Campbell, Lost among the Affghans 1862 which has been digitilized by Google) who was a British baby found at Tezeen along the route of the 1841 retreat and raised by the Wali of Kunar. Campbell later returned to his own people in India, which undoubtedly must have been a significant cultural shock for him. Campbell wrote an account of his experiences amongst the Afghans. However, some British women simply decided to marry Afghan men and enjoy the delights of remaining in Afghanistan “and their grandchildren still are living. But the grandchildren of the British women everyone knows because they have red hair and white skin.” (page 17-18 Dupree First Anglo Afghan War Folklore and History 1974). They would not be the last British women to abandon their country men in favour of Afghan men ( see Schofield, Victoria Every Rock Every Hill).

Returning to 1840s Afghanistan, the Puppet Ruler placed on the Kabul throne, Shah Shuja survived until April1842 when he fell to an assassin’s bullet. In Afghan memory Shuja’s name will forever be tainted with being a British collaborator and someone who was considered unlucky, which means today no self respecting Afghan would give the name Shah Shuja to their son.

The British did not simply leave Afghanistan after the disastrous retreat, the East India Company was thirsting for their pound of flesh. The East India Company recruited traditional enemies of the Afghans such as the Mahrattas to serve in the new forces being assigned to wreak their revenge on Afghanistan. The British consequently returned to Afghanistan in 1842 and massacred the unfortunate citizens of Kabul, Charikar and Istalif. In Istalif all men above the age of puberty were executed and many of the women raped. In the words of a young British officer, Neville Chamberlain,

“Tears, supplications were of no avail; fierce oaths were the only answer; the musket was deliberately raised, the trigger pulled and happy was he who fell dead”(See G W Forrest , Life of Field Marshall Sir Neville Chamberlain page 144).

The Sepoys would also occasionally burn wounded Afghans( See A Fletcher

Afghanistan Highway of Conquest page 118) In the current conflict US Psy Ops Troops deliberately attempted to cause religious offence by desecrating the dead bodies of two Talibs and pointed the feet in the direction of Mecca and setting the bodies alight whilst taunting local villagers in Pashto( see The Guardian 21/10/2005). Muslims believe in prompt burial of the deceased with the feet facing Mecca but cremation has no part in Islamic rituals and the US Psy Op troops were mocking Islamic burial rituals.

On their way back to India Pollock’s army seized the doors from the Tomb of Mahmud of Ghazni and took these to India because they wrongly believed that these doors were from a Hindu temple at Somnath. The Governor General of India, who sought to win favour with the majority Hindu population, erroneously presented the doors as being those of the Temple of Somnath and the Governor General said Hindustan had been avenged! The fact that Indian Muslims did not share the Governor General’s sentiments was of course ignored.

Consequences of this War

Had chivalry died?

Arnold Fletcher in Afghanistan Highway of Conquest, a neutral US historian, provides an interesting analysis of which side in the Anglo Afghan wars adhered to the rules of chivalry and thereby held the moral high ground:

Page 117: “the Afghans emerge with rather more credit than their opponents...their(Afghan) actions were mild ...Only a few prisoners were harmed, and no English women were raped...The destruction of the army in the Khurd Kabul was a ghastly affair, but most of the victims died with weapons in their hands, and the weather was as much responsible for the great mortality as the Afghan knives.”

In contrast the British slaughtered civilian populations in Charikar, Istalif and Kabul and took no prisoners on their retreat “and the many rapes by sepoys and British soldiers set no example upon which to build a case against the Afghans (Fletcher page 118).”